The pride in doing something together - Interview with Renzo Piano

Renzo Piano tells us about the bridge he designed for Genoa to replace the viaduct over the River Polcevera.

Renzo Piano tells us about the bridge he designed for Genoa to replace the viaduct over the River Polcevera.

Born in Genoa, Italy in 1937, after receiving his high school diploma, Renzo Piano went on to graduate from Milan Polytechnic in 1964. He then opened a design studio in London with Richard Rogers where they designed the Pompidou National Art and Cultural Centre in Paris, also known as the Beaubourg. In 1981 he inaugurated the Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), which has offices in Genoa, Paris and New York, and in 1989 he was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. His project portfolio includes the Kansai International Airport in Osaka, the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre in New Caledonia, the head offices of the New York Times in New York and of the Italian newspaper Il Sole24 Ore in Milan, the Auditorium Parco della Musica in Rome, the Muse Science Museum in Trento (Northern Italy), the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens and the Paris Court of Law. In 2013 he was nominated Senator for Life by the Italian President at the time, Giorgio Napolitano.

Thank you for answering a few questions about the construction of the new bridge in Genoa, in which Mapei has also taken part.

Before we start, I would like to say something. I know Mapei perfectly well and I have worked with them on many projects, including the hospital we are building for Emergency (an UN-recognized international non-governmental organization) in Uganda (see Realtà Mapei International no. 63), which unfortunately has had its official opening ceremony put back to probably the end of the year. Together with Mapei we have carried out some great work in Uganda, where we have worked directly on the clay being used to build it, gone down to Lake Victoria to collect samples, taken them to the laboratory, tested them and worked on them together. I followed the design and the construction of the hospital from up close with Gino Strada, the founder of Emergency. Now, because of the lockdown, work has been forced to slow down. I find it really interesting to talk about the hospital and the work that has been carried out on the materials. And I would like to point out that, right from the very start of this project, Giorgio Squinzi (former CEO of the Group) and the Mapei staff focused their efforts on the work carried out in the laboratory. Every time I meet someone from Mapei we end up talking about research into materials, which is something I really like discussing. It’s a great way to work.

What went through your mind when the Mayor of Genoa, Marco Bucci, asked you to intervene in the hours immediately following the collapse of the Polcevera Viaduct?

At times like that it isn’t easy to think straight: I was really saddened by what had happened. On the 14th of August I was following a project in Switzerland and I was absolutely stunned. The next day I spoke with the Mayor and this sense of suffering hung over us, and then this feeling was something that seemed to be always hanging over the site. This tragedy has always been on our minds and has never been forgotten, but all the helpers – and I use this word in its widest sense to include everybody, from designers to chemical engineers to general labourers – have a certain characteristic, and that is, they know how to react. And without ever forgetting that this project was borne out of tragedy and suffering, we have all tried our best to imagine what could be done. What is more, a bridge that collapses is a terrible thing, and in this particular case it was the cause of 43 deaths, 500 people were forced to abandon their homes and a city was split into two. When a bridge collapses it can also make people feel as if their own world is falling apart, because a bridge should never collapse.

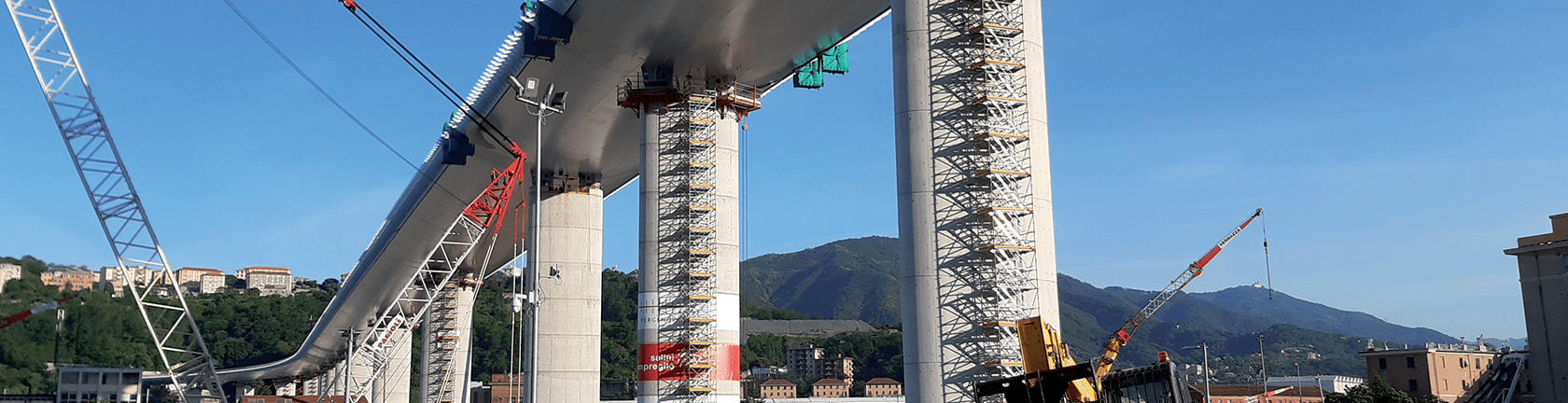

When the Mayor called me that day, my first thought wasn’t to come up with a project or a design; it was to try and lend a hand and see what could be done straight away, taking into consideration that the viaduct was 50 m above ground level, which by itself is something to be taken really seriously. We then slowly worked towards the idea of finding a solution that could be achieved quickly, which is why we immediately thought about how to divide the entire site into two large but separate sites. One of the sites would take care of logistics, that is, the builders and demolition teams which started working straight away, to create the new foundations and the 50 m high piles. Working in parallel would be the site where the shipbuilders were operating. And while all this was going on, the Magistrates had to carry out their investigation. So, as you can see, it was a very, very complex operation, but I have to say that, thanks to the effort and will of everybody, everybody, everybody (Renzo Piano repeated the word three times with so much conviction, Ed.) we managed to do it. And from the first to the last person on site, from the Commissioners to the general labourers, everybody worked in chorus, something which often happens when working on site. This was a site where it was clear, right from the very start, that you were participating – with enormous pride – in a grand feat of engineering, in every sense. And with this spirit, where people came together around a project involving so many different skill-sets, including the expertise in chemistry of Mapei technicians, it really was a magnificent effort. I want to emphasise in the strongest terms that this wasn’t a miracle. In Italy we have the ability and capacity to carry out such feats of engineering through companies that export their skill and expertise all around the world. But, all too often, these skills only seem to emerge during an emergency, and I find this very sad.

Did you ever consider, even at the beginning of the operation, to try and conserve at least part of the bridge?

Absolutely, this was also one of the hypotheses we looked at, but it was put to one side. Firstly, the magistrates would have had to put a stop to everything for one or two years, or even more, which is exactly what happened. Then again, the magistrates have to do everything in their own time and the bridge had to be left as it was so they could carry out their investigation into what was truly a disaster. Then another problem arose: it was difficult to establish how much of the structure left standing was safe. We thought about it and talked about it for ages, but to hook up to the old structure was technically impossible. I really loved that bridge; it was a part of the period of optimism and, as a young architect, I always looked at it with great respect. But mistakes may have been made when it was constructed, we really couldn’t tell at that moment.

When we thought about the possibility of mending the bridge – something I like to picture in my mind – well, it wasn’t absolutely impossible. A number of years ago, along with Mapei, we carried out a study on the Flaminio Stadium in Rome, designed by the Pier Luigi Nervi design studio, using only thin layers of concrete and only a minimum amount of concrete cover around the rebar. In that specific case it was more like a restoration job, like mending the stadium, by intervening only on the structures to consolidate them and protect the rebar. In the case of the Morandi bridge, however, something tragic had occurred, which from a justice standpoint still hasn’t been resolved. So, as far as the approach was concerned, we were right to have at least thought about it. The route of the new bridge has also been modified slightly, in order to be able to make new foundations without interfering with the old ones.

There has always been a constant dialogue with the city as your designs gradually develop. Did you follow the same pattern with the new bridge? And what idea of the city were you confronted with?

What we have designed and built is an urban bridge that is almost asking for the city’s permission to pass through it. An urban bridge that has planted its supports, every 50 m, where it can, in a densely populated part of the city. This is also because a span of 50 m is an intelligent span when it comes to construct the steel deck. This span of 50 m for the new bridge was adopted 15 times and then, when it reaches the Polcevera area and the area around the station, the span is doubled, and the length becomes 100 m. An urban bridge that doesn’t cross a valley with untamed vegetation, but one that passes through a valley where people live, that is inhabited, and brimming with activity. Like a large white ship sailing across a valley, with its curved form, seen from below, that seems to be playing with the light. At first glance it seems very thin, a lot thinner than it really is, because a good 18,000 tonnes of steel were used for the bridge.

There is, however, a relationship with its surroundings. This is a motorway bridge which should one day become an urban bridge from a legal standpoint because, if the Gronda motorway is constructed, it will be declassed and become an urban structure. The bridge also has lighting, something motorway bridges don’t have.

I would like to stress that I am a designer and I have made my contribution, but here there was the contribution of thousands of specialists and there was a very intelligent approach from a logistics and organisational point of view, which is why it took only one year to build a bridge. Something not to be taken for granted. I built another bridge in Ushibuka in the south of Japan. A bridge one kilometre long, just like this one, and it took us three years. A bridge is a long, complex structure and it usually takes around 3 to 4 years to build. So, to build a bridge in one year required a highly sophisticated logistics organisation and building site and highly organised team work.

Can you give us a brief overview of the construction phases of the bridge, starting from the work carried out on site which never stopped, in spite of the difficulties you had to overcome because of such a complex situation?

That is a very good point. During the lockdown, work on site, which was considered to be of primary importance, never stopped. At a certain point a member of the team became Covid-19 infected. He was immediately identified, along with the people he had come into contact with, and they were placed in quarantine. And the site carried on working. From an organisational point of view, it was a very delicate job, like fitting together all the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle: basically, we had to demolish the old bridge to get ready for the new one. Then, we had to start laying the foundations for the new bridge while the old bridge was still standing! So, all the logistics sides had to be prepared and also all the piling for the new foundations that wouldn’t go on the old foundations because they had a completely different span, and there is even a slight difference in the route it takes around the bend to the west along the right-hand bank. So all these operations had to be organised and, in the meantime, work started on the steelwork for the bridge in two large Fincantieri sites, using steel brought in from Taranto (Southern Italy) at just the right thickness. It was like a jigsaw puzzle: if all the work had been carried out in sequence, a project of this type would have taken 3 to 5 years. Here, on the other hand, everything was arranged and fitted together at the same time thanks to an incredible team effort!

The word I prefer using for the new bridge is “rapidity”. The bridge was built very rapidly, but not hastily, because, as they say, haste makes waste. I was particularly struck by the way the work was coordinated, and also by everybody’s enthusiasm and their pride in doing something together with a common interest. During my visits to site, which is something I always enjoy, I was always particularly struck by the team spirit.

An entire section of the urban fabric of Genoa will also be getting a new look, thanks to the redevelopment of an area of 80 hectares which has been tendered out to a group comprising Stefano Boeri, Metrogramma Milano and Inside Outside founded by Petra Blaisse. Were you also hoping for a solution of this type?

I am often in touch with Stefano Boeri; a tender was issued, and it is a group effort involving architects, landscape architects and botanists. It’s a lovely project, we call it a “park” in an urbanistic sense, but in reality, it will be a space that will be lived and inhabited by people. The bridge is 50 m above the level of the river and has this curved form which allows the light to filter down; it is not a bridge that remains in the dark underneath where nothing manages to grow.

On 30th June this year you received an award in honour of your career, “For the professional and civil commitment that has distinguished and continues to distinguish your architectural output”.

If an architect never asked himself why he does what he does, it would be very worrying. Architecture is the art of constructing spaces for people, so it has a clear social and collective function. And then let’s not forget that “politics” comes from the Greek word polis, which is the art of administering cities. Which means architecture is the art of construct cities.