Interviewee

Carlo Blasi

Works Management Consultant for the restoration work

We spoke with Professor Carlo Blasi, Works Management consultant for the restoration work: project drawings by Eugène Violet Le-Duc and the construction works journal to bring the cathedral in Paris back to its original glory.

Professor Blasi, you have been involved in the restoration and reconstruction work of the roofs and vaulted ceilings of Notre Dame Cathedral, and particularly in overcoming the problem of structural stability. What operations were carried out on the vaulted ceilings of the Cathedral?

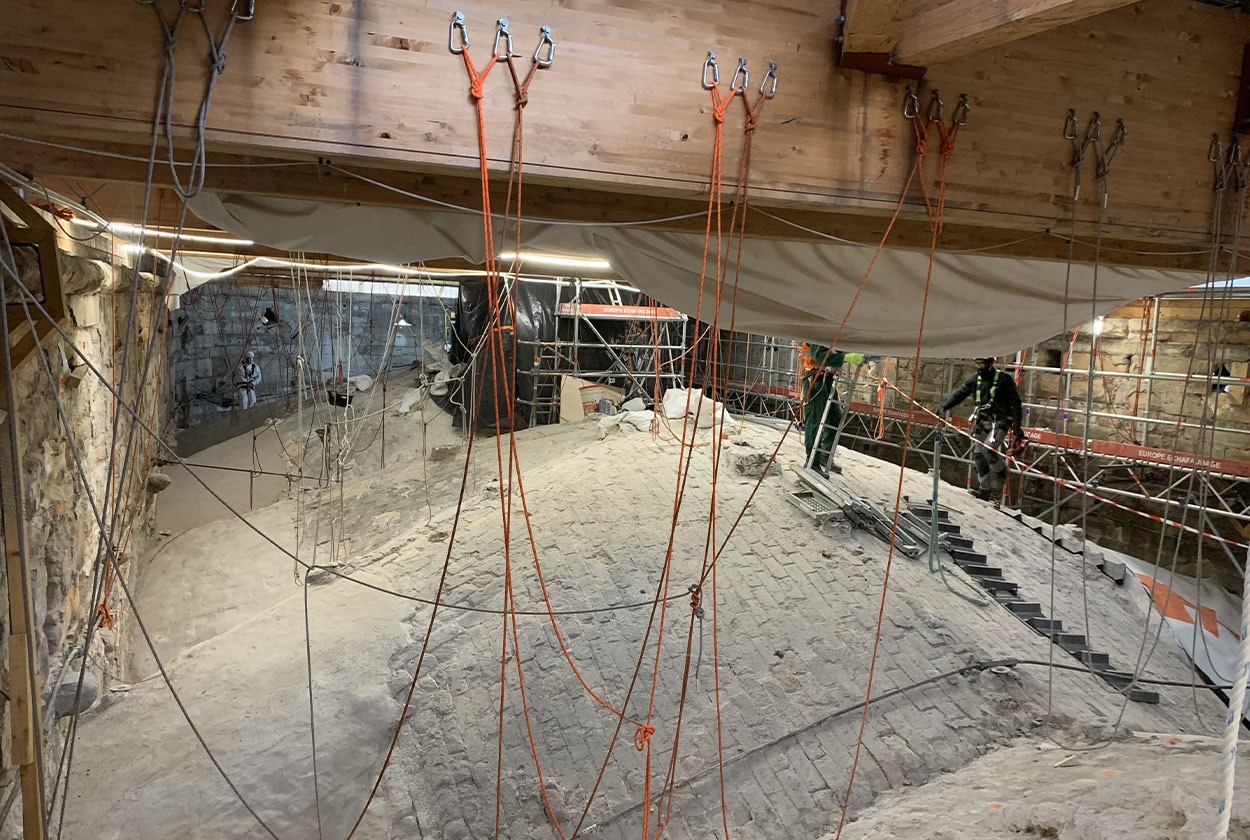

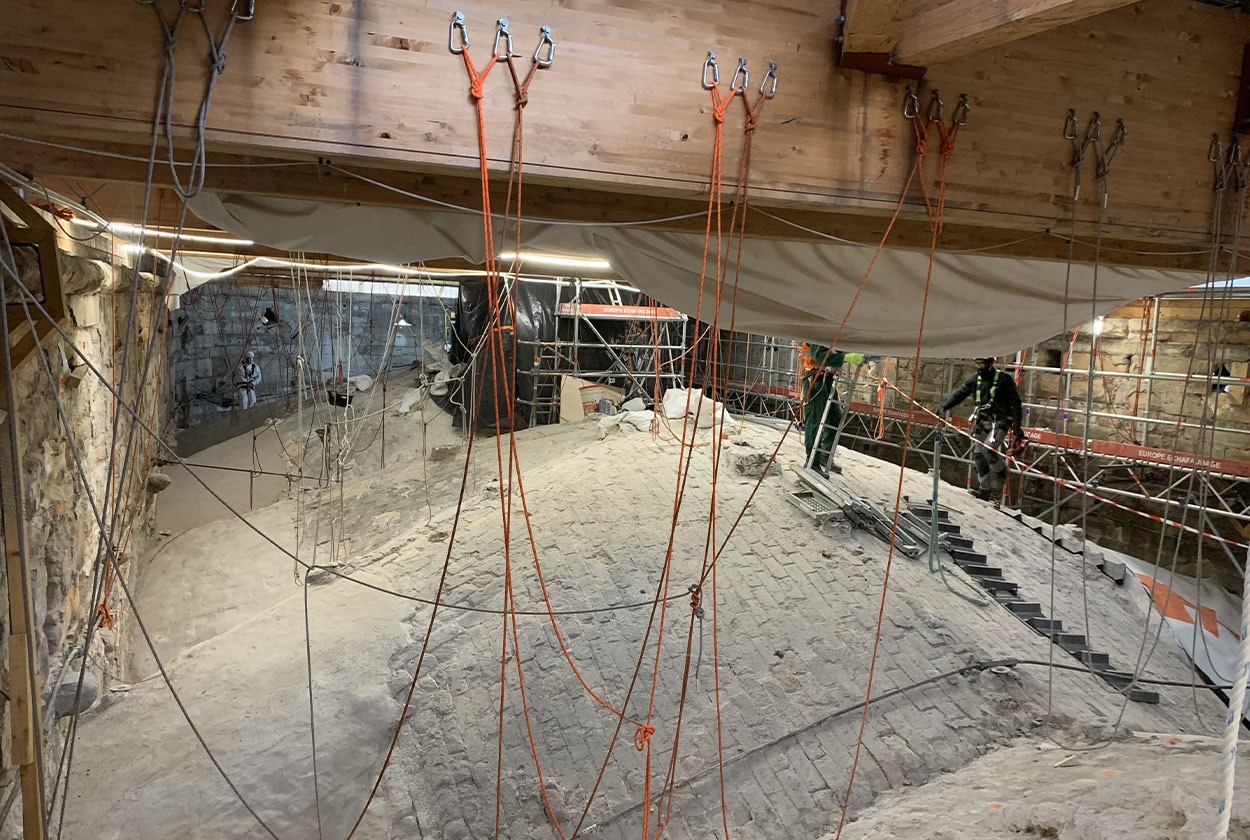

On the Notre Dame site we carried out both construction and restoration work because part of the vaulted ceilings, such as the ceiling of the central cross vault and part of the ceiling of the transept, had collapsed so had to be reconstructed, whereas the ceilings that remained standing needed to be consolidated. They had been damaged on the extrados by the fire and were suffering from delamination: in many cases the upper part had become detached and internal cracks were found. So, we carried out consolidation work to give them the strength required and to restore their original thickness.

What exactly were the problems you encountered regarding structural stability?

From an overall structural perspective, the fact that a good part of these vaulted ceilings had been there for 800 years was already a guarantee, and more reliable than any virtual modelling. Notre dame Cathedral had no particular cracking or subsidence problems, apart from to a small degree at the top of the walls: we can say that, over the centuries, the physiological behaviour of the structures had been good. The problems were so not so much to do with stability, that is, what would happen if we reconstructed the vaulted ceilings to how they were originally as required by the French Ministry of Culture; it was more of a case of verifying which parts were dangerous and needed to be removed so as not to have weak points, so any of the stones that had moved during the collapse and were no longer stable were removed and replaced with new stones of the same type.

We also had to remediate the damage to the extrados of the vaulted ceilings and this is where Mapei products came into play. Before the fire this zone had a gypsum render layer, which is a material widely used in France. The render layer had protected, at least partially, the vaulted ceilings because gypsum is a very good thermal insulator, but a lot of the cap had been lost in the fire. After carefully analysing all the solutions available, it was decided to use a type of mortar that would faithfully reproduce the original thickness (or even increase it by 1-2 cm), but with structural properties gypsum would not have been able to guarantee. So it was decided to opt for a type of mortar that would also guarantee good strength and resistance inside the joints where the original mortar had been “cooked” by the fire. This cooked mortar was removed, the joints were stripped out down to a certain depth and PLANITOP HDM RESTAURO mortar was applied in the joints and over the whole surface of the extrados.

(C) MAPEI France

Why was it decided to use fibre-reinforced mortar?

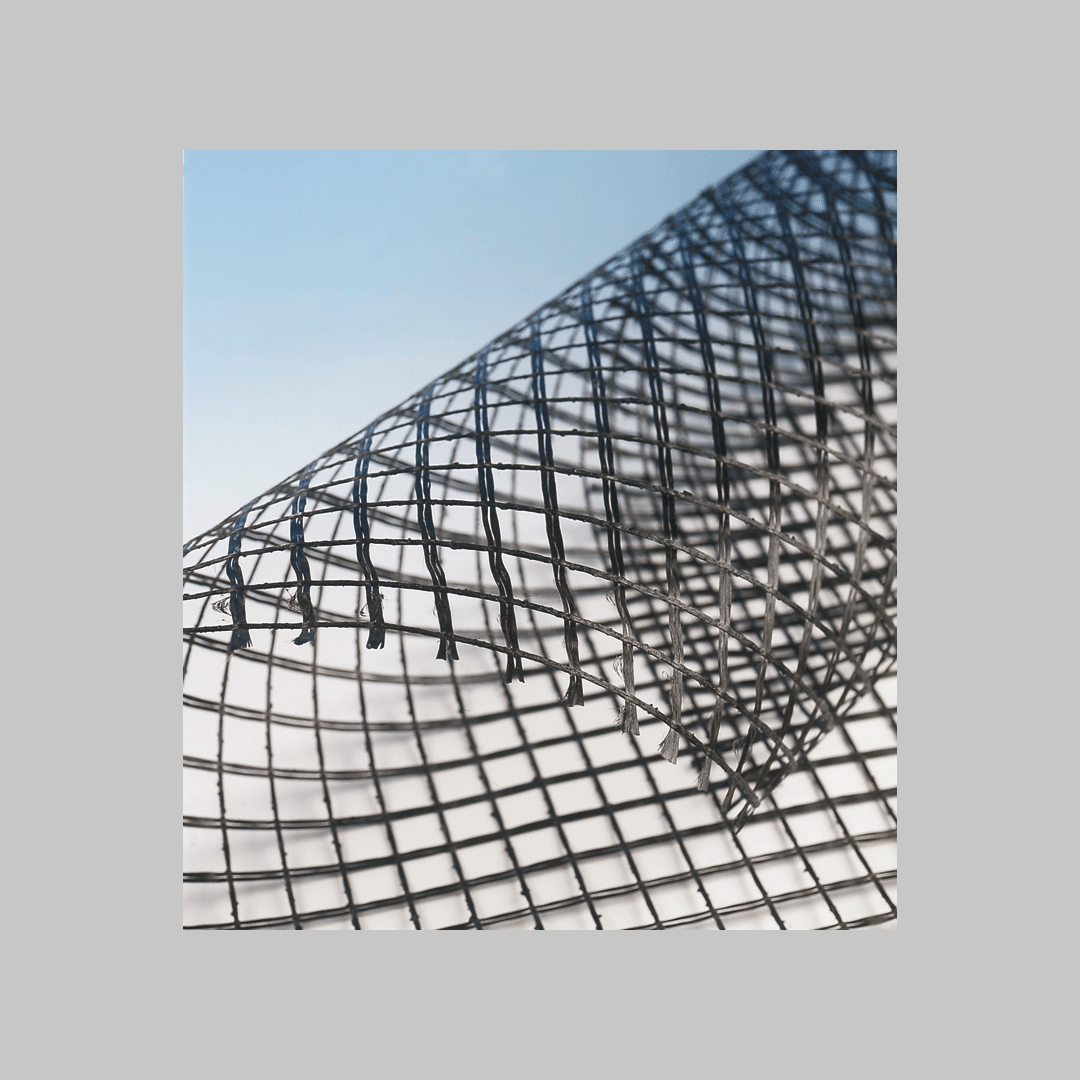

It was a necessity due to the condition of the structures where it was applied: it was not only the surface that had to be reconstructed, but the mortar also had to go into the joints and anchor firmly to the inside of the joints to guarantee a sufficient level of shear and tensile strength. Tests were also carried out to check how easy it would be to apply the mortar in the joints by creating sample caps out of products from different companies. The results of these tests showed how PLANITOP HDM RESTAURO was more effective and easier to apply than other products.

Working at height with a safety harness. (C) MAPEI France

What other criteria led to PLANITOP HDM RESTAURO being chosen?

One of the prerequisites was to use hydraulic lime, so the fact that this product is made from natural hydraulic lime and eco-Pozzolan certainly played a part in its selection. It was also necessary to guarantee its compatibility with gypsum because, as I said previously, this material was used in the joints. In addition, Mapei’s extensive experience of using mortars for consolidation and restoration work was greatly appreciated. Mapei was able to demonstrate that its materials had been tested, had undergone various tests and that they had been awarded certification for their mechanical properties and characteristics and were not, as in the case of products proposed by other companies, aerated lime-based mortars to which fibres had simply been added, and were without (or had very little) documentation regarding their properties and mechanical characteristics.

Apart from PLANITOP HDM RESTAURO, “L” shaped glass fibre anchors supplied by Mapei were used for the work in zones where it was feared the stones could have internal cracks not visible to the naked eye, as was demonstrated after taking core samples. The capacity of a single company to supply several solutions was much appreciated, also because, with respect to the proposals from other suppliers, it was a clear indication of Mapei’s more extensive experience of working on restoration and structural strengthening projects.

And lastly, the presence of Mapei technicians that came to carry out tests on site was fundamental. Their support, expertise and availability truly were determining factors in choosing the most suitable materials. For example, the fact that the materials were prepared by people who knew them well underlined their competitive advantage compared with the other products proposed during sampling and testing. What is more, Mapei experts instructed the users on how to handle and apply the materials correctly, which helped them feel more confident, encouraging a spirit of collaboration between the various parties and generally improving the mood on site.

The experience of an Italian company and an Italian architect and professor had an important role in the restoration of the cathedral. What do we owe this experience to and how is it viewed in France, particularly by the various actors involved in the restoration of Notre Dame?

The experience Italy as a nation has in restoration and structural strengthening work is undoubtedly extensive and is due to the fact that, because of the earthquakes and sheer number of ancient monuments all around Italy, our country as a whole and our professionals have had to develop their skills and have far more understanding than elsewhere. Thanks to the high number of historic buildings that are restored and reconstructed in Italy, we have the necessity to provide stability and strength for our monuments that other countries, which are not so badly affected by earthquakes, do not have. And also, when it comes to norms and standards, in Italy we have more specific regulations and this has a virtuous effect on all those working in the structural sector who have gained experience, both theoretical and practical, that is not so ingrained abroad. This involves all manufacturing companies who need to supply materials that comply with these specific standards and requirements in terms of properties and yield.

What other problems were caused by working on a building with such a long history and that is part of the artistic and cultural heritage of the French capital and of the entire nation?

As I said previously, right from the very first surveys we found the structures were pretty stable and this was due to the skill of those who built the Cathedral and which, over the centuries, had guaranteed their stability. For example, the work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was fundamental who, following the damage caused during the French Revolution, carried out reconstruction and consolidation work by inserting numerous iron chains to tie the perimeter walls together, and even placed them inside the walls themselves. This operation meant that any instability in the load-bearing structures observed after the fire (apart from the damage caused by the fire itself) was very modest.

A pressing problem, on the other hand, was the need to also guarantee the reliability of the consolidation work to the insurance companies. The system we are used to nowadays to guarantee the stability of newly constructed buildings is to carry out structural calculations and virtual modelling which, for masonry buildings with a centuries-old history, is not very reliable because they could give contrasting results due to the uncertain hypotheses regarding the mechanical behaviour of the materials and programmes used, which Italian legislation acknowledges. In fact, Italian standards suggest a careful approach when using these virtual methods and, in the case of work on historic buildings, require a detailed, written report about the solutions proposed which takes into account the real behaviour over the centuries.

In France, however, there is not the same level of experience on this topic, so the tendency is to rely on and trust the results of calculations and modelling. I, however, insisted on the fact that 800 years of history was already concrete proof of a structure’s stability, something much more reliable than virtual modelling or a numerical calculation. So I managed to convince the authorities involved that reconstructing the building to how it used to be originally was, in itself, a guarantee of stability for future years. Reconstructing the cathedral to how it used to be before the fire and its collapse, therefore, was the best approach to guarantee the structure would be sufficiently stable also in the future, for at least another eight hundred years. So, because the objective was to restore the Cathedral to its condition before the fire, it was decided to create a new render layer using a type of mortar such as PLANITOP HDM RESTAURO, which seemed to be the most suitable to recreate the thicknesses and mechanical strengths of the original vaulted ceilings.

Wooden arches at the cross-point of the transept that enabled the reconstruction of the diagonal arches and the oculus of the oculus of the vaulted ceiling. (c) Romaric Toussaint_Rebatir Notre Dame de Paris

So, the decision to “reconstruct to how it used to be” was not dictated by aesthetic or artistic considerations, or as a matter of principle, but it was also due to functional needs regarding the stability of the building.

All the authorities involved immediately agreed that the final appearance of the Cathedral had to be as similar as possible to how it used to be before the fire. At first, President Macron had said there would be a tender and, as a result, there was an “avalanche” of proposals, and it soon became clear that going through a public tender process would be very risky and that this historic icon had to be recreated. Sometimes, reconstructing buildings to bring them back to their original appearance does not, however, guarantee adequate safety levels.

For Notre Dame we looked into the possibility of reconstructing the roofs in steel or concrete, but then it was decided to reconstruct them to how they were previously. For the wooden parts, the decision was quite easy for two reasons: very thorough research work had been carried out to collect information and also referred to the design drawings by Violet Le-Duc and the construction works journal. In addition, the results of numerical calculations on the wooden structures (far simpler and more reliable than those carried out on masonry structures) had basically confirmed that these structures still performed their function well, even when applying currents standards.

So both the original design with its ultra-centennial history and modern numerical calculations confirmed the effectiveness of the original solution and, therefore, the rationality of re-proposing a structure that had also been successfully tested by centuries of efficiency.

For the masonry, as I said, there was a certain degree of added uncertainty due to the difficulty and reliability of the theoretical calculations and assumptions. For example, when carrying out calculations on deformability, between real data recorded for structures over the centuries and data obtained using virtual modelling, there can often be large differences. It was not easy to convince all the professionals involved to “Have faith in the history” of the Cathedral, but in the end, we managed to. Merit, probably, of the extensive experience in Italy of restoring and consolidating historic buildings. So Notre Dame will return to being stable, just how it used to be.

It was not easy to convince all the professionals involved to “Have faith in the history” of the Cathedral, but in the end, we managed to. Merit, probably, of the extensive experience in Italy of restoring and consolidating historic buildings.

Born in Florence in 1948, he graduated with honours in Architecture in 1972. He then went on to become a researcher in the field of Construction Science and Technology at the University of Florence and Associate Professor in Restoration at Bari Polytechnic. From 2002 to 2014 he was Full Professor in Restoration at the University of Parma. From 2013 to 2017 he was a serving member of the Italian National Commission for Public Works.

He currently carries out his profession at the Studio Associato Comes architecture and engineering firm, of which he is joint owner, and holds lessons at the Ecole de Chaillot school of architecture in Paris.

His research work and professional activities focus mainly on structural design, restoration work, the stability of historic buildings and seismic protection solutions. He also worked as a consultant on projects to safeguard architectural heritage for UNESCO, the World-Bank and the governments of numerous countries (such as France, Japan, Morocco and Syria). He has worked on many important monumental buildings in Italy and abroad: restoration work on the Citadel of Damascus, the stability of Saint Sophia Cathedral in Istanbul, the reconstruction of Mostar bridge, the safety and integrity of Adolph Bridge in Luxembourg, the reconstruction and consolidation of the al-Nuri Mosque and minaret in Mosul, the stability of the temple complex of Angkor, the Panthéon in Paris and the Cathedral and Baptistery in Florence and the reconstruction of the Petruzzelli Theatre, as well as the reconstruction of numerous buildings following the earthquakes that hit Emilia and Le Marche.

He is currently working on the reconstruction project for the Basilica of San Benedetto in Norcia and the consolidation of the Basilica of San Miniato al Monte in Florence and has been commissioned by the French Ministry of Culture to study the problem of structural stability as part of the reconstruction of Notre Dame.

He is also author of numerous scientific papers.